Something quite remote from anything the builders intended has come out of their work, and out of the fierce little human tragedy in which I played; something none of us thought about at the time: a small red flame - a beaten-copper lamp of deplorable design, relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; that flame burns again for other soldiers, far from home, farther, in heart, than Acre or Jerusalem. It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.Ok, perhaps I'm investing a little too much meaning in a painting of an old lamp. Simply take it as an example of the convoluted ruminations that keep me company most of the time. 9" x 12", watercolor, drybrush, pen and ink, on Fabriano cold-pressed 140 lb. paper.

Friday, February 27, 2009

The Light in the Temple

From a scene at the farm in Vermont, this old lamp, hanging from a rusty nail, was originally blue. My younger son Sam, surveying the photos from which I was working, noticed the discrepancy and asked why I had chosen red over the pale blue. I explained that it would be a stronger, more expressive image with a red lamp, and reminded him of our visit to the Rubin Museum of Art (specializing in items from the Himalayas and surrounding regions), where we learned that red is the color of power. I think his eyes glazed over when I started talking about how this simple camp lantern could be analogous to one of the lamps in a Tibetan temple, or even a Christian church. Indeed, my initial thoughts on this theme were drawn from the final scene in Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, as Charles Ryder returns to the small family chapel at the Brideshead estate:

Friday, February 20, 2009

From the Archives at my office . . .

One would think that a New York City organization founded in 1848, one with a rich history of involvement in this neighborhood of Manhattan, might have a respectable archives cataloging its history. Unfortunately, that's not the case here. Indeed, there are official records, diaries, meeting minutes, photographs, blueprints - and god only knows what else - scattered higgledy-piggledy in drawers, closets and cabinets throughout this 1906 building.

(And I should note that this isn't unusual. As a historian I encountered soooo many institutions/associations, some with histories stretching back 200 years, that had taken little or no care in preserving their records. If you're in a business that generates a great deal of paper, you understand the dilemma. What gets saved? Sure, it's easier in a digital age. But New York City still has mobile paper-shredding trucks that shred tons of documents every day. Thus my indignation over poorly preserved and/or badly organized records is always tempered with an understanding of the difficulties inherent in the archival process.)

I found this photo tucked away in a storage cabinet, sharing space with bound copies of Harper's magazine from the 1880s and 90s. It's ca. 1910 and documents the "Free Vacation School" offered to neighborhood children. Close inspection reveals a pretty diverse group, including an African-American boy on the front row and an African-American girl at the rear. Right away one knows that this is not a southern institution! Beyond this photograph, I've seen no other records about the "Free Vacation School" program. (And I have no idea what that netting is for. Any ideas? I don't think it's a product of the "raffia" listed on the sign. In fact, the raffia makes sense in the context of the "basketry" offered as an activity for the children.) By the way, the front of the building looks exactly the same today. My office is behind the leaded-glass windows to the left. (Click on the image to view a larger version.)

(And I should note that this isn't unusual. As a historian I encountered soooo many institutions/associations, some with histories stretching back 200 years, that had taken little or no care in preserving their records. If you're in a business that generates a great deal of paper, you understand the dilemma. What gets saved? Sure, it's easier in a digital age. But New York City still has mobile paper-shredding trucks that shred tons of documents every day. Thus my indignation over poorly preserved and/or badly organized records is always tempered with an understanding of the difficulties inherent in the archival process.)

I found this photo tucked away in a storage cabinet, sharing space with bound copies of Harper's magazine from the 1880s and 90s. It's ca. 1910 and documents the "Free Vacation School" offered to neighborhood children. Close inspection reveals a pretty diverse group, including an African-American boy on the front row and an African-American girl at the rear. Right away one knows that this is not a southern institution! Beyond this photograph, I've seen no other records about the "Free Vacation School" program. (And I have no idea what that netting is for. Any ideas? I don't think it's a product of the "raffia" listed on the sign. In fact, the raffia makes sense in the context of the "basketry" offered as an activity for the children.) By the way, the front of the building looks exactly the same today. My office is behind the leaded-glass windows to the left. (Click on the image to view a larger version.)

Thursday, February 19, 2009

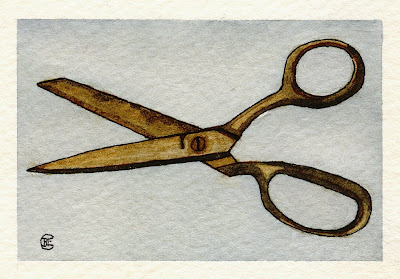

Rusty Scissors

Latest in the series of "ordinary objects." The bits of black on the handles were supposed to be remnants of black enamel paint, but I think the matte finish of the black is too flat and thus doesn't suggest the depth and shine of a black enamel. Perhaps an overpainting of acrylic would have remedied this. Alas, something to remember for the future. 5" x 7" watercolor, pen & ink, brush & ink, on Fabriano cold-pressed, 140 lb. paper.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Art Cards: Rusty Scissors

I recently discovered "art cards" and learned that people trade and sell them. There are oodles on Etsy and Ebay, with cards sold by painters, photographers, collage artists . . . you name it. So I figured, why not? But the 2 1/2" x 3 1/2" format seems a bit daunting for a painter. Here's my first effort - rusty scissors - which will serve as a miniature study for a slightly different 5" x 7" version that I'm painting for the "ordinary objects" series. I had to wear my strongest glasses to do this! It's 2 1/2" x 3 1/2", watercolor, pen and ink, on Strathmore cold-pressed, 140 lb. paper. (In this horrible art market, I guess it makes sense to produce works that are accessible for buyers at all price points. Face it, with prices down across the board and the biggest auction houses and galleries having trouble selling their wares, does it make sense to produce strictly giant canvases if one is trying to put food on the table. Even the smaller galleries that dot the Chelsea landscape are finding it difficult to market moderately priced artists. What's a starving artist to do?)

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Vintage Mixer

Here's the latest in the series of "ordinary objects" that I've been painting in anticipation of creating a set of notecards for a future Etsy site. As with the others, this is a 5" x 7", watercolor with pen and ink, on Fabriano cold-pressed paper.

Friday, February 13, 2009

While walking to work this morning . . .

Nothing spectacular here, especially in terms of composition. Just some snapshots of the views I encountered on Fifth and Park Avenues this morning.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Monday, February 9, 2009

Broken Windows - In Memory of Andrew Wyeth

Looking through Andrew Wyeth's painting following his recent death, I was reminded how nice the drybrush technique could be. But I also knew it could prove time-consuming as one worked to find that perfect - albeit minimal - amount of moisture to transfer the pigment to paper. Too much water and one loses the drybrush effect. Too little and it becomes difficult to dab more than a few faint, wispy strokes with each loaded brush. (Sometimes the faint brush strokes are desirable, of course.) Executed correctly, however, drybrush proves perfect for rendering texture and depth in a piece. When not using his preferred egg tempera medium, Wyeth would use drybrush for landscape and architectural textures that can prove elusive in straight watercolors. In "Geraniums," for example, Wyeth used a combination of watercolors and drybrush to paint a through-the-window study of Christina Olson.

This painting, my first attempt at incorporating the drybrush technique into my work, is based on a series of images I took along Route 10 in Virginia's Isle of Wight County. I knew that watercolor washes just wouldn't give me the desired weathered texture of the window frame. I debated whether or not to allow enough light in the picture to reveal hints of the building interior. In the end, I preferred the reflected opaqueness of the intact windows with only the tattered curtains visible, while leaving the interior dark - and thus a bit mysterious or foreboding. 9" x 12", watercolor, drybrush, pen and ink, on Fabriano paper.

This painting, my first attempt at incorporating the drybrush technique into my work, is based on a series of images I took along Route 10 in Virginia's Isle of Wight County. I knew that watercolor washes just wouldn't give me the desired weathered texture of the window frame. I debated whether or not to allow enough light in the picture to reveal hints of the building interior. In the end, I preferred the reflected opaqueness of the intact windows with only the tattered curtains visible, while leaving the interior dark - and thus a bit mysterious or foreboding. 9" x 12", watercolor, drybrush, pen and ink, on Fabriano paper.

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Ernest Flagg

Shooting photos of interesting architectural elements recently, I ran across a couple of buildings that immediately grabbed my attention. The Singer Manufacturing Company building, a 12-story structure, was designed by Ernest Flagg and completed in 1904. Flagg's design represented a departure from the thick masonry walls and small windows that defined architectural style at the time. The Singer building would feature an innovative structure of iron and glass, with floor-to-ceiling windows offering far more light than other buildings. Even its colors - red and green - proved innovative exceptions to the dull marbles and granites that punctuated New York's streets.

Today the building holds co-op residential units and commercial spaces. It received a renovation in the late 1990s that included significant work on the facade.

Mills House No. 1, in photos 2 and 3, is on Bleecker St. between Sullivan and Thompson Streets. Completed in 1897, the 11-story Mills House, designed to provide inexpensive housing for men in the city, it had 1,560 single-room-occupancy spaces that were no more than 5 by 7 feet in size. When it opened, the hotel charged 20 cents a night, and 10 to 15 cents a day for meals. (Mills also built two other single-room-occupancy hotels in Manhattan.) Converted to apartments in the 1970s, Mills House No. 1 became a co-op building in the 80s.

Although I didn't know it at the time I was taking these photos, Mills House No. 1 was also designed by Ernest Flagg. This structure doesn't possess the more innovative design elements of the later Singer Manufacturing Company building, but did reflect Flagg's keen interest in "fireproof construction, daylight, ventilation and housing policy."

Today the building holds co-op residential units and commercial spaces. It received a renovation in the late 1990s that included significant work on the facade.

Mills House No. 1, in photos 2 and 3, is on Bleecker St. between Sullivan and Thompson Streets. Completed in 1897, the 11-story Mills House, designed to provide inexpensive housing for men in the city, it had 1,560 single-room-occupancy spaces that were no more than 5 by 7 feet in size. When it opened, the hotel charged 20 cents a night, and 10 to 15 cents a day for meals. (Mills also built two other single-room-occupancy hotels in Manhattan.) Converted to apartments in the 1970s, Mills House No. 1 became a co-op building in the 80s.

Although I didn't know it at the time I was taking these photos, Mills House No. 1 was also designed by Ernest Flagg. This structure doesn't possess the more innovative design elements of the later Singer Manufacturing Company building, but did reflect Flagg's keen interest in "fireproof construction, daylight, ventilation and housing policy."

Monday, February 2, 2009

INRI

Since taking up painting several years ago I've given a lot of thought to the issue of religious subjects. And while I've painted a couple of stained glass window images, I didn't regard them as overtly religious images. Several times I contemplated images depicting some aspect of the nativity of Jesus, but none of my ideas proved truly resonant, and thus strong enough to inspire a painting. I especially didn't want to create an image of Jesus that could be compared in any way to the ridiculously idealized Christian imagery of Warner Sallman, whose paintings of Jesus because the most widely distributed images of Jesus in the United States in the 1940s and 50s. Indeed, just about any Christian imagery would prove problematic given my opinions on the more zealous factions of the faith. These views I've made clear on numerous other occasions in this website. As I said in March 2007:

So, where does this leave me, possessing a higgledy-piggledy spiritual DNA, a double helix of agnosticism, Southern Baptist childhood, Episcopal adulthood, casual flirtations with Buddhism and Quakerism, as well as a fascination with some of the more ascetic and insular religious sects, including the Hassidim and the Amish? . . . Complicating the matter, I also represent that segment of the liberal populace that thinks "fundamentalist Christians," particularly those who identify with the Republican party and have tried to manipulate its agenda through groups like the Christian Coalition, are America's answer to 1930s fascism. These people - and not Islamic-based terrorist cells - are the most dangerous group in this country . . . but nothing new, given our nation's long history of breeding religious extremists.

That having been said, in the end, I jumped straight to the crucifixion, aiming for a more gothic representation without going so far as to imitate some of the more graphically violent aspects of Christian imagery from the Iberian tradition. No blood-soaked forehead and bleeding wounds here! And as usual, I had to take that narrowly focused perspective that only provides a hint of the whole. To be honest, I couldn't have painted the entire crucifixion from head to toe, let alone include the thieves flanking Jesus. Nevertheless, I think it retains a strength - a pathos - while avoiding some of the more "kitsch" elements of Protestant iconography.

While some observers might interpret this painting as a reflection of my own faith, it does not represent a devotional exercise in the way the creator of a gilded icon sees his effort as a form of worship. It's more an experiment - a monochromatic exercise in my development as a painter. Moreover, I've never been comfortable painting the human form, especially in a portrait setting, and this image in many respects falls into that category. Technical details: Sepia watercolor with pen and ink, on 5" x 7" Fabriano hot-pressed paper. (And for those of you not familiar with the meaning of "INRI": Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum . . . Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.)

So, where does this leave me, possessing a higgledy-piggledy spiritual DNA, a double helix of agnosticism, Southern Baptist childhood, Episcopal adulthood, casual flirtations with Buddhism and Quakerism, as well as a fascination with some of the more ascetic and insular religious sects, including the Hassidim and the Amish? . . . Complicating the matter, I also represent that segment of the liberal populace that thinks "fundamentalist Christians," particularly those who identify with the Republican party and have tried to manipulate its agenda through groups like the Christian Coalition, are America's answer to 1930s fascism. These people - and not Islamic-based terrorist cells - are the most dangerous group in this country . . . but nothing new, given our nation's long history of breeding religious extremists.

That having been said, in the end, I jumped straight to the crucifixion, aiming for a more gothic representation without going so far as to imitate some of the more graphically violent aspects of Christian imagery from the Iberian tradition. No blood-soaked forehead and bleeding wounds here! And as usual, I had to take that narrowly focused perspective that only provides a hint of the whole. To be honest, I couldn't have painted the entire crucifixion from head to toe, let alone include the thieves flanking Jesus. Nevertheless, I think it retains a strength - a pathos - while avoiding some of the more "kitsch" elements of Protestant iconography.

While some observers might interpret this painting as a reflection of my own faith, it does not represent a devotional exercise in the way the creator of a gilded icon sees his effort as a form of worship. It's more an experiment - a monochromatic exercise in my development as a painter. Moreover, I've never been comfortable painting the human form, especially in a portrait setting, and this image in many respects falls into that category. Technical details: Sepia watercolor with pen and ink, on 5" x 7" Fabriano hot-pressed paper. (And for those of you not familiar with the meaning of "INRI": Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum . . . Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)